Paintings, Pointe Shoes, Movies, and Spirituality: What Governments Should Know if They Want More Active Citizens

By Maria Francisca Costa, Sciences Po—Menton

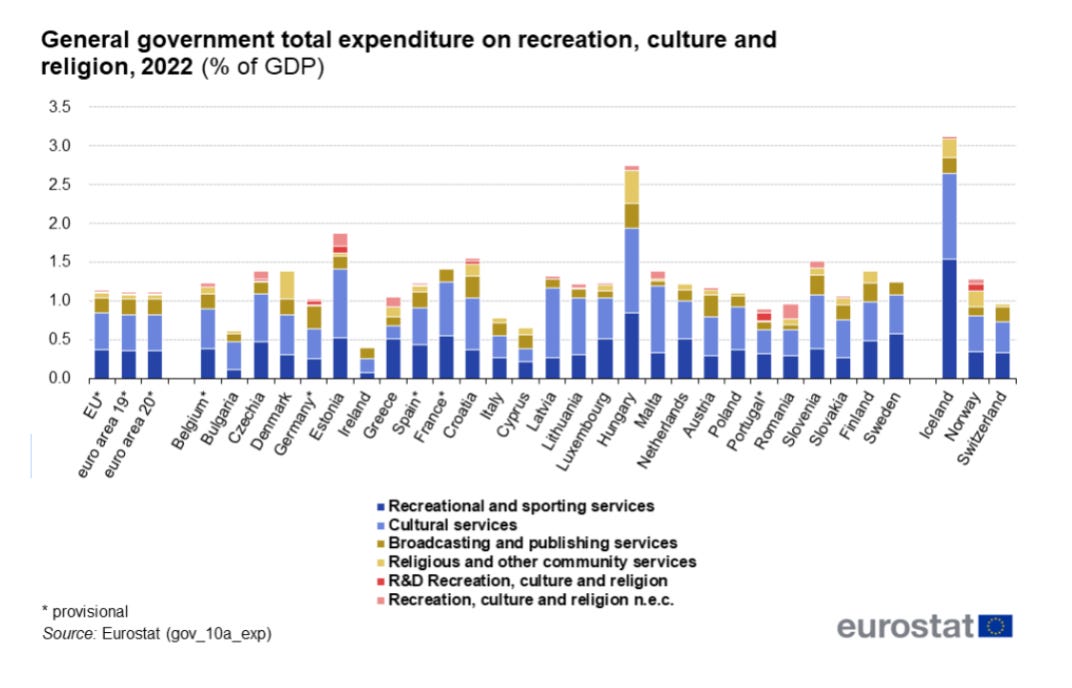

In the European Union, government spending on cultural activities— spending on recreational and sporting, cultural, broadcasting and publishing, and religious and other community services, as well as as series of other religious and cultural activities—varied somewhere between just under 0.5% to just above 3% of GDP, as of 2022. While Ireland and Iceland are the exceptions to each respective threshold, most countries allocate 1-1.5% of their GDP to the cultural sector, with the EU’s average being a little more than 1%.

Eurostat reports that these values have peaked in 2007 and in 2008 and achieved their lowest in the period of 2020-2022, deductively due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Recent research shows that citizens’ participation in cultural activities strengthens “civic engagement, democracy, and social cohesion”, and it also helps to build social ties among people with different backgrounds. In 2008, the United States’ National Endowment for the Arts described a “sizable overlap in populations that attend arts events and do other kinds of civic and social activities.” However, even under the assumption that cultural participation strengthens civic engagement, can we say the same for governmental spending on cultural activities? To answer this question, analysis must focus on the relationship between governments’ cultural spending and cultural participation. Does the former necessarily cause an increase of the latter? If not, what can be done to promote civic engagement within the cultural landscape?

This article will define the term “cultural participation” as follows: “The receptive and creative conscious activities through which people increase their informational and cultural baggage as far as four different cultural domains are concerned: Cultural Heritage, Performing Arts, Books and Press, Audio and Audiovisual Media and Multimedia”. The concept of “civic engagement” is understood as “the behaviours and attitudes through which people express their willingness of interacting within the community and contributing to its well-being, as far as four dimensions are concerned: Political life, Civil society, Community Life, and Civic Sense”.

Participation in Cultural Activities and Civic Engagement

A 2020 paper, Does Culture Make a Better Citizen? Exploring the Relationship Between Cultural and Civic Participation in Italy, analyzed the relationship between cultural participation and civic engagement in Italy. Their study found cultural participation to be a reliable predictor of a citizen’s civic engagement. Namely, “this positive effect is slightly stronger for people who are highly involved in a large variety of cultural activities”. This study suggests that “attending or practicing cultural activities” strengthens individuals’ social capital - defined as “the social resources one possesses as a result of one’s social network”, and which “have the potential to influence behaviour”. Additionally, even though“cultural participation remains positively and significantly associated with civic participation” across educational levels. A 2024 study published by the EU, “Culture and Democracy, The evidence,” found that citizens’ cultural engagement enhances their “likelihood to vote, to volunteer, and to participate in community activities, projects and organizations”. In 2009, researchers from the National Endowment for the Arts found similar patterns of cultural and civic engagement in the United States of America. They concluded that U.S. citizens who “attend arts performances, visit arts museums or galleries, or read literature” stand out for their community engagement.

Government Spending on Culture and Cultural Participation

Under the assumption that increased cultural participation would promote civic engagement, it would be expected that any measures taken by European governments to boost the popularity of cultural activities among their citizens would also contribute to forming more civically engaged citizens. Thinking of government expenditure as the most direct way to strengthen cultural sectors, it is of great use to make a brief comparison of levels of government spending on culture and citizens’ cultural participation across Europe.

Figure X gathers data collected from the Eurostat on both categories. The level of governments’ spending on the cultural sector is explained through governments’ expenditure towards “Recreation, Culture, and Religion”, as a percentage of a given country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Cultural participation is measured through the indicator “People participating in cultural activities at least once in the previous 12 months”, as of 2015.

Figure X

Figure X illustrates a seemingly weak relationship between the two variables. The countries spending the most—Estonia and Hungary—on their respective cultural sectors are not those presenting the highest values of cultural engagement. Conversely, the countries spending the least—Ireland and Italy—are not those where the population’s level of cultural participation is the lowest.

In 2015, Estonia and Ireland presented, respectively, the second highest (2.0%) and the lowest (0.6%) levels of government expenditure on culture. However, these two countries presented similar levels of cultural engagement, with Estonia’s reaching 69.8% and 69.3%. It is therefore of most importance to compare these two countries’ governmental policy outside of monetary investments to understand their similar levels of cultural participation.

Estonia

There were almost 250 museums in Estonia as of 2012. Since the end of the 20th century, many cultural buildings have been constructed. Authors Lagerspetz and Ali argue that “the maintenance of an established set of cultural institutions has remained the basis of cultural policy” in the country. In fact, four years previous to the data analyzed, in 2011, little less than a half of the budget allocated by the Estonian government to the cultural sector “consisted of expenses for professional theatres, museums, libraries, sports schools and centres, and state-run concert organizations.”

In the early 2000s, a “working group on culture industries” was established in the Estonian Ministry of Culture. According to experts, “the focus of cultural policies on the creative industries” accompanied “a growing bureaucratisation, and becoming an important danger for government funding of the arts.” After strategy reforms in 2023, the government initiated “a practice of granting support to specific projects in-stead of subsidising the industry on a permanent basis.”

Ethnic Estonians represent 68% of Estonia’s population, with the minorities’ share being primarily divided between Russians, Germans, and Swedes. Although the existence of multiple NGOs has diversified Estonia’s cultural life, the country’s cultural sector seems to lack a strategy to respond to the country’s ethnic diversity. Lagerspetz and Tali argue that, in Estonia’s cultural strategy, there is a “tendency to present culture as a part of a common, ‘national,’ cause,” which not all can identify with. This arguable lack of policy inclusivity is so far unable to be met by minority organizations: “Even if the number of different organisations for minority cultures is large, they have remained very small in size, and their ability to reach out to the members of minority groups is limited.”

In the libraries’ sector, a 2012 policy was widely criticized for its failure to respond to readers’ demand for “popular literature.” This policy allocated “50% of state subsidies to municipal libraries for the purchase of books and journals considered important to Estonian culture.”

Nonetheless, state expenditure on cultural institutions seems to be useful in establishing strategies to boost cultural participation. Many museums in Estonia have created “education and outreach departments” to facilitate programs that target children and the youth. On the other hand, some of the country’s museums allow “free access on the last day of every month.”

Finally, despite a rapid growth of civil society organizations in the Estonian arts’ field since the end of the 1990s, some point out a lack of strategy to tackle this sector. The government lacks a “uniform practice” to consult non-governmental organizations for policy-making purposes. There is also “a tendency among governmental agencies (including the Ministry of Culture) to stick to those organisations with an earlier record of smooth cooperation” which can hinder innovation within the field.

Ireland

Promoting cultural participation is one of the main goals of Ireland's strategy in the cultural sector. Many museums in Ireland do not charge an entrance fee, including the National Museum of Ireland and the Irish Museum of Modern Art. A “Learning and Engagement Group” has been created in the Council of National Cultural Institutions. This group “includes representatives from the education, participation or engagement teams/departments of each institution”, being “a forum for sharing policy and practice across the institutions”

The government’s goal in strengthening cultural participation seems strongly sustained by a strategy to keep children and youth engaged with the cultural sector. Specific exhibitions that may charge individual fees are free for minors and for full-time students. The government also institutionalized this goal by creating the Free Educational Visits for Schools Scheme, which enables students across all levels of education to visit some cultural heritage sites for free. Music Generation, a national program dedicated to the teaching of music to younger generations, was created in 2009. This program seeks “to transform the lives of children and young people through access to high quality performance music education in their locality”.

Ireland’s cultural scene presents many initiatives that simultaneously aim to develop the sector, and also promote the involvement of civil society, and vice-versa. The Arts Council was founded as the “Irish government agency for developing the arts”. The Council’s Arts in the Community Scheme “offers funding for artists and community groups of place/or interest to work together on arts projects.” Its main objective is to “encourage meaningful collaboration between communities of place and/or interest and artists.”

As of 2009, about 10% of Ireland’s ordinary residents had a foreign nationality. The Irish government’s policy in the artistic domain also entails a special attention given to the country’s cultural diversity. The Arts Council launched the policy framework Cultural Diversity and the Arts to operationalize this goal. It also created an Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion Toolkit more recently to provide an actionable framework for artistic organizations targeting minorities and diverse communities.

Estonia and Ireland: What Can We Learn?

Despite their significantly different levels of public expenditure as a share of GDP, Estonia and Ireland’s populations present similar levels of cultural participation. This is due to their respective governments’ strategy towards the cultural sector being of an essentially different nature. While Estonia’s government seems to focus on monetary investments, Ireland’s is focused on policy frameworks specifically aimed at involving the public. Another key difference between these strategies is that Ireland seems to be more effective in targeting a wider public by introducing policy frameworks directed at incorporating the country’s diversity. Conversely, Estonia faces the challenge of incorporating a similar framework into a cultural system that is made appealing through the lens of Estonian cultural heritage. Finally, the Irish government has established more mechanisms to involve new civil society initiatives, while Estonia’s cultural strategy has remained essentially centralized.

These examples illustrate that increased government spending in the cultural sector does not necessarily entail a better chance for governments to boost citizens’ cultural participation. We can therefore deduce that increased spending in this area should not be made a priority if governments aim at boosting countries’ civic engagement. Policy frameworks aimed at welcoming innovation, involving civil society organizations, and incorporating the country’s diversity, on the other hand, seem to be a more effective choice for governments for this purpose.

Conclusion

The relationship between government spending on culture and civic engagement seems to be weak. However, we know that a stronger cultural engagement is an important predictor of more involved citizens. It seems therefore useful to further investigate how government strategies concerning the cultural sector can be framed to maximize the involvement of civil society in the cultural sphere, as well as to wide the access to cultural activities to more, and diverse, sectors of the population. As of now, we know that easily accessible, inclusive cultural activity is a good promise of a more civically-engaged citizen.

Cover photo taken from Fanny Schertzer.