Urban Fault Lines: The Impact of Urban Divides on Social Cohesion and Economic Mobility in Global Cities

By Avery Bespalko, University of Toronto

In cities worldwide, urban fault lines—social and economic divides—shape the urban landscape, creating fragmented communities within the same metropolitan area. These divisions profoundly affect access to resources, economic opportunities, and social cohesion, perpetuating cycles of inequality. By examining São Paulo, Johannesburg, and Toronto, we can gain insight into the consequences of these divides and explore strategies for more inclusive urban planning.

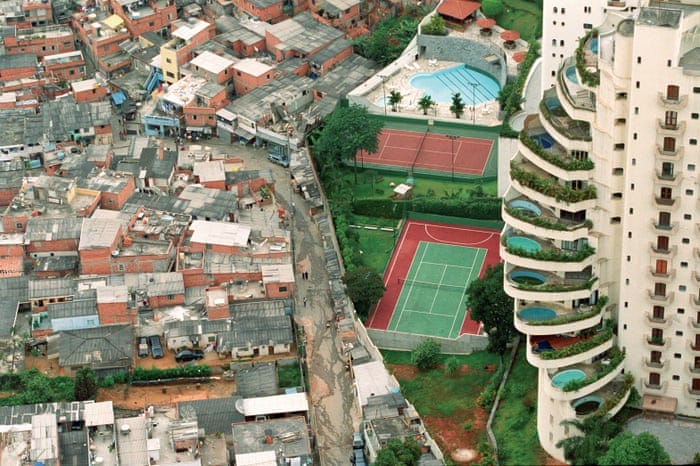

Figure 1: São Paulo’s Inequality, Paraisópolis Favela, São Paulo, Brazil.

Note: The photograph illustrates the contrast between the favela Paraisópolis and a wealthy neighborhood, highlighting urban inequality in São Paulo. From “São Paulo's stark inequality: The story behind the iconic photograph of Paraisópolis,” by Guardian News and Media, 2017, The Guardian.

What are “Urban Fault Lines”?

Urban fault lines refer to socio-economic and racial divides that fragment urban spaces into distinct areas. These divisions are often rooted in historical zoning laws, economic disparities, and systemic inequalities, creating pockets of wealth and poverty. Over time, these fault lines have solidified, shaping the way residents access services, engage in their communities, and move through the city.

In Toronto, the “three cities” framework developed by David Hulchanski illustrates the impact of these urban fault lines. According to Hulchanski, Toronto has split into three distinctive “cities”: “City One” encompasses affluent neighborhoods with rising incomes, “City Two” is characterized by middle-income areas with stable income levels, and “City Three” includes low-income neighborhoods where incomes have consistently fallen. This stratification underscores Toronto’s challenges with economic inequality, racial segregation, and unequal access to resources.

Similar divisions exist in São Paulo and Johannesburg, where social and racial inequalities are also deeply embedded in the urban fabric. In São Paulo, high-income enclaves sit side-by-side with informal settlements (favelas), resulting in stark contrasts in living conditions and access to services. Comparatively, Johannesburg’s spatial landscape is still heavily influenced by its apartheid legacy, which enforced strict racial segregation and social-economic disparities. While de jure racial barriers have been dismantled, income inequality remains stark, particularly among Black residents who often find themselves confined to less affluent neighborhoods. The shift from an industrial to a service-oriented economy has further exacerbated this divide, with high-paying jobs predominantly available to a small elite. State housing initiatives like Cosmo City have introduced some diversity, but market forces continue to perpetuate segregation. Consequently, Johannesburg’s ongoing efforts to address these inequalities through measures like densification and inclusionary housing face significant challenges.

It is important to note that these urban divides are not accidental; they have been shaped by decades or even centuries of planning policies that favor some areas over others. Toronto’s “three cities” divide, for example, emerged over a long period due to urban planning choices that concentrated wealth in certain areas while neglecting others. In São Paulo and Johannesburg, colonialism and apartheid established lasting patterns of segregation, creating neighborhoods that, despite their proximity, might as well be worlds apart in terms of opportunity and quality of life. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle where specific neighborhoods receive fewer resources, lack high-quality public infrastructure, and become isolated from economic centers.

The Impacts of Urban Divides on São Paulo, Johannesburg, and Toronto

Urban fault lines have profound consequences for city residents, influencing access to essential resources and opportunities.

In São Paulo, affluent districts like Moema and Itaim Bibi benefit from abundant services, green spaces, and quality infrastructure, while peripheral areas face overcrowded schools, limited healthcare, and unreliable transit. A 2007 quality of life survey highlighted these disparities, showing that central districts generally have much higher levels of development. São Paulo neighborhoods such as Moema, Pinheiros, and other wealthy districts surpassed a Human Development Index (HDI) of 0.95, similar to countries like Sweden and Canada. Meanwhile, poorer districts like Marsilac and Jardim Ângela scored between 0.70 and 0.75, comparable to a country such as Guyana. Additionally, Brazil as a whole has one of the world’s highest Gini coefficients, reflecting extreme income inequality throughout the nation and São Paulo is no outlier in that sense.

Johannesburg’s urban fault lines are closely tied to its apartheid history, with wealthier, predominantly white suburbs maintaining a higher standard of living than the predominantly Black townships. The geography of Johannesburg exacerbates these divides, as under-resourced townships like Alexandra remain isolated from the economic activity in areas like Sandton. Access to jobs, quality education, and healthcare remain limited in these marginalized neighborhoods, reinforcing the socio-economic disparities established decades ago.

In Toronto, “Hulchanski’s “three cities” framework highlights how wealth and poverty are spatially distributed across the city, influencing residents’ access to resources and quality of life. “City Three” neighborhoods, which are often home to marginalized communities, face challenges like inadequate public transportation, underfunded schools, and more limited healthcare services. This spatial distribution of wealth not only isolates residents but also limits their economic mobility, as lower-income areas are often far from job centers and high-quality services.

Additionally, these divides can lead to social consequences, such as the stigmatization of certain neighborhoods. In Toronto, residents of “City Three” may face social prejudice due to their addresses, which can impact everything from employment opportunities to social interactions. In São Paulo and Johannesburg, informal settlements and townships are sometimes viewed by wealthier residents as areas of crime or disorder, reinforcing stereotypes that contribute to social isolation and reduced political voice for residents in these areas. These perceptions can make it harder for residents to advocate for necessary services, as stigmatization often silences or legitimizes their demands for equitable treatment.

Efforts to Bridge Urban Fault Lines and the Challenges that Arise

Cities are making some attempts to reduce these divides through urban planning and social policy. However, the relative effectiveness of these efforts varies.

In São Paulo, initiatives like Programa de Urbanização de Favelas (Favelas Urbanization Program) have focused on improving conditions in informal settlements through infrastructure upgrades, better sanitation, and enhanced housing. While these efforts have brought improvements to residents’ quality of life, they often struggle to address deeper economic inequalities and, at times, face criticism for inadvertently displacing residents due to rising property values and insufficient protections.

Johannesburg has implemented similar strategies, such as the Corridors of Freedom initiative, designed to bridge urban divides and increase social cohesion by connecting marginalized neighborhoods with economic hubs. This ambitious transit-oriented development (TOD) sought to address the legacy of apartheid-era spatial divides by fostering inclusive economic growth and reducing travel times of township residents. However, challenges like inadequate funding, limited affordable housing options, and inconsistent private investment have hundred the program’s impact. Political changes further compromised the initiative, reducing its scope and weakening its initial promise of transformation. The Corridors of Freedom highlights the complexities of addressing entrenched urban fault lines, revealing how limited resources and political instability can undermine efforts to enhance social and economic mobility in global cities.

Toronto has taken steps toward bridging its “three cities” divide through affordable housing and transit-oriented development. A key example is the Eglinton Crosstown Light Rail Transit (LRT), which is aiming to enhance public transit access for lower-income communities. While the LRT promises to reduce travel times for residents, there are growing concerns about gentrification and displacement as the area becomes more attractive to developers. As development applications surge, it is essential to ensure that the move towards improved transit fosters social cohesion and promotes equitable economic mobility rather than displacing the community.

Another strategy that cities like Toronto have adopted involves creating public-private partnerships to fund affordable housing developments. For example, Flemingdon Park faced considerable economic and social challenges, prompting initiatives aimed at revitalizing the community while preserving its affordable housing stock. Collaborations between public agencies and private developers sought to enhance housing options by integrating new, mixed-income developments that subsidized units alongside market-rate housing. While these partnerships can lead to improved infrastructure and amenities, they also carry the strong risk of social cleansing, as rising property values and living costs may displace long-term residents; the same worry that is echoing across the aforementioned Eglinton Crosstown LRT line. Ultimately, revitalizing urban areas while preserving the communities that currently inhabit them is a highly complex and nuanced endeavor.

Moving Forward: Solutions for Inclusive Urban Development

To create more inclusive cities, urban planners and policymakers must adopt holistic strategies that address root causes of inequality. The following three approaches can be used to guide future efforts:

Invest in Equitable Urban Policies: Policies that address foundational disparities–such as education, healthcare, and economic opportunity–are essential for breaking cycles of inequality. In Toronto, for instance, increased funding for schools and healthcare facilities in “City Three” neighborhoods can help equalize access to resources and opportunities.

Empower Community-Led Development: Community-led projects ensure that development reflects residents’ needs and values. By involving residents in the planning process, São Paulo and Johannesburg can implement changes that serve marginalized communities rather than displacing them.

Measure Impact with Data-Driven Approaches: Quantitative data allows cities to assess the effectiveness of policies and hold urban planners accountable. By tracking indicators like income distribution, housing costs, and access to resources, cities can monitor progress and make necessary adjustments.

A comprehensive approach might also include the use of zoning reform to integrate neighborhoods and create more affordable housing across urban areas. Zoning laws have historically been used to enforce racial and socio-economic divisions but by reforming these policies, cities can break down barriers that restrict marginalized communities to certain areas. Furthermore, progressive taxation on high-value properties or vacant land could generate funds for social programs in lower-income neighborhoods, addressing systemic inequalities without burdening the poorest residents.

Urban fault lines fragment cities all over the world, isolating communities and perpetuating socio-economic divides. The “three cities” framework in Toronto, alongside similar divides in São Paulo and Johannesburg, highlights the pervasive impact of urban divides on residents' lives. Addressing these divides requires comprehensive, data-informed strategies that prioritize inclusivity, equity, and community engagement. By addressing urban fault lines, cities can foster more connected, resilient, and equitable environments for all residents.

Amazing Read!